The Way of the Samurai

Tradition in Japan celebrates grace, tranquility, and harmony with nature. But tradition also celebrates the fierce warriors of Japan, the samurai. Their era lasted for more than a thousand years, only ending in the middle of the 19th century. Sometimes wandering alone in search of fame and wealth, more often fighting in Japan’s complex civil wars, the samurai may well have been history’s most terrifying and effective warriors.

Was it pure technique, mere physical mastery of the sword, that made the samurai so deadly? Or had they unlocked near magical sources of strength and courage through the contemplation of beauty and nature? Was this why the samurai were able to wield their weapons with the focused intensity that has made them legendary? Were they effective because they were unrestrained and undistracted by the fear of death?

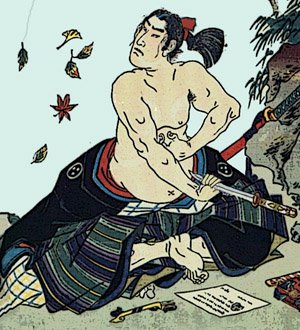

Warriors in every culture are trained to be brave in the face of death. What made the samurai unique was that they often chose to die. If defeated in battle or disgraced by some other failure, honor demanded suicide. But the samurai could not kill himself as others might, by poison or slashing his wrists. Tradition demanded a grizzly ritual called Seppuku, or Harakiri. The samurai plunged his knife deep into the left side of his abdomen, drew it across his midsection, and then finished with an upward pull of the blade. Death from such a wound can take hours or even days. Why did the samurai choose this particular form of excruciating death?

In fact, few men even though they were samurai could actually complete their own disembowelment. To ensure this final act went smoothly, a friend stood ready with a sword. At the first sign of hesitation or distress, in a final act of friendship, the swordsman sliced off the samurai’s head. At this crucial moment, the very instant of death, great care was taken to spare witnesses any sight, which might seem indelicate or offensive. To the modern western sensibility, the samurai may seem an impenetrable mystery, but they were human, with their own unique view of life and death. The word samurai means to serve, and this is how the samurai began, as warriors in the service of the emperor of Japan.

A country divided by steep mountain ridges, Japan was difficult for a central government to subjugate and rule. The emperor needed a clan of mounted warriors who could move swiftly to enforce his authority in even the most remote villages. Eventually the emperor’s warrior servants realized they could be the masters themselves. By the year 1300, the samurai had taken control over the provinces and districts they had once administered for the emperor. Like the knights of medieval Europe, the samurai built castles and established hierarchies among themselves. Samurai warriors served samurai generals, and generals served samurai warlords.

For much of Japan’s history, the emperor was a respected figurehead with no real power. Having established themselves in their various domains, the warlords began to fight each other with armies of samurai warriors. They fought for their lord, to expand his lands and increase his power. There was however something else at stake, something greater, the warrior’s personal honor. To what bizarre length would the samurai go to preserve his honor?

For over 300 years, beginning in the 14th century, Japan was wracked by periodic civil wars. But even large battles often consisted of simultaneous individual duels. Warriors needed to know the merits of each other before the fight began so they could be properly matched. There was a practical reason for this seemingly fanatical concern with honor. Samurai status could be inherited, but for much of Japanese history, any man could declare himself a samurai. To actually secure employment with one of the warring factions however, he had to establish a reputation and maintain it. Even the leather armor often worn by the samurai did more than protect them. It proclaimed their presence, this was a warrior to be reckoned with.

Face guards and masks enhanced the samurai’s fierce demeanor. Some heroes however, chose to demonstrate their disdain for danger by appearing serene in the midst of combat, with painted lips and rouged cheeks. Battles begun and fought with such style and honor could end in only one way, with a death of one of the fighters. Whether killed outright or committing suicide in acknowledgement of defeat, death on the battlefield almost always entailed decapitation. The concern for severed heads may seem like a grotesque and savage obsession until we discover the reason behind it. The head was a refutable proof an enemy had been killed. The victorious samurai would be rewarded by his master with land and other gifts.

To prepare for battle, the samurai carried a small arsenal of weapons: Bow and arrow, a lethal variety of spears, lances, and knives. Even a fan, so often the very emblem of delicate gentility, was made with iron ribs so that it could be used to parry the thrust of an attacking lance or sword. Of all this deadly array, it was the sword that eventually became the paramount weapon of the samurai. In part, this was because as warlords became more powerful, they fielded ever larger armies. When the battlefields became crowded, a close-ranged weapon was necessary, and it was a fearsome weapon indeed.

Methods of sword making evolved throughout the centuries, but the essentials remain unchanged. Steel heated to the color of the morning sun was folded and pounded repeatedly, each fold doubling the layers. Four foldings produced sixteen layers. Eight produced sixty-four. The finest finished swords contained as many as 1,000,000 layers. It is this which gives the sword it’s unique flexibility, sharpness, and strength. Mastering so deadly a weapon demanded years of training and a lifetime of unrelenting practice.

In time, the sword became the very emblem of the samurai’s status and more, it was endowed with mystical qualities. But what happened to humanity and conscious when a man merged his soul with that of his weapon? Many samurai were deeply troubled by their lives of killing. Many were Buddhists, and there inlay a wrenching dilemma. Buddhism preaches cycles or birth and rebirth, with each life depending on the virtues and sins of the life before. A samurai saying held that their punishment was to be reborn in the next life yet again as a samurai.

For many in the West, the very model of the traditional Japanese women is obedient and gentle, but there is another side to her. Women warriors were rare, but there was nothing remarkable about women holding samurai status. Once a man became a samurai, the distinction was usually passed down to all his descendants, male and female. Women samurai ran a household which was often a large and complex farming operation. However, during the wars which periodically raged throughout Japan, the distinction between home and battlefield sometimes disappeared. If the man were off on a distant campaign, the women were expected to mount a fierce defense. Defense, household management, and the production of heirs, samurai marriage was largely a practical affair with little romance. Often the marriage represented a political alliance, and political alliances were notoriously unstable.

Much about the samurai confounds conventional expectations about a warrior’s life. The warrior was also a poet. It was common samurai practice to calmly compose a poem before committing suicide or going into battle. While a simple lyrical farewell poem often served to stiffen the courage of a samurai facing death, the achievements of a warrior artist like Miyamoto Musashi became legendary. His paintings and sculptures are a treasured part of collections throughout Japan. Musashi was also a master swordsman. The same hand which created this exquisite artwork cut down as many as sixty men. Musashi’s accomplishments may have been extraordinary, but his devotion to both fine arts and martial arts was not unique. Indeed, the samurai made little distinction between the two. This is why even Ikebana, the ritual arranging of flowers, was regarded by the samurai as a martial art. This art trains one’s mind to become one with the flowers, the same way in which he would become one with the sword.

Within this world of beauty and bravery however, there was another world, a shadow world where all values were reversed. It was inhabited by men who wore no proud insignia and moved in silence, the ninja. Although a distinction is often made between ninja and samurai, ninja usually were of samurai class, serving as spies and assassins. Other than that, little reliable information about them exists. How great a role did the ninja play in the rise and fall of the great samurai households? How many deaths attributed to illness or accident were really their work? The truth will probably never be known.

Long after China and other parts of Asia had become known to Europeans, the remote islands of Japan remained forbidding and mysterious. Then, in 1542, a Chinese ship arrived at Tomogashima Island in the south of Japan. The ship’s crew included Portuguese sailors, the first Europeans to arrive in Japan. Everything about these strange visitors excited the interest of the Japanese, most particularly their weapons. An eyewitness account describes the spectacle, “In their hands, they carried something two or three feet long. Straight on the outside, with a passage inside, and made of a heavy substance. They fill it with powder and small lead pellets. The explosion is like lightning and the sound like thunder.”

The samurai lord of Tomogashima Island promptly bought two of these intriguing new weapons and set his chief sword maker to duplicating them. At first, most samurai disdained the new weapon, in part because men using them could fire from a distance without the face to face confrontation demanded by a sword fight. However, as has happened so often in history, tradition eventually gave way to technology. Within 50 years, the Japanese were making more guns than any country in Europe. At the same time, Japan was moving toward consolidation, as a few great warlords subjugated their neighbors. The campaigns culminated in the year 1600, in the Battle of Sekigahara. At Sekigahara, it was gunpowder that won the day for the forces of the warlord Tokugawa Ieyasu, whose dynasty would rule Japan, finally united and at peace.

To protect the new stability, the dynasty declared Japan closed and sealed it from the outside world. Almost all foreigners were expelled. Foreign ideas, foreign religions, and foreign weapons were banned. Soon, the making of guns seized almost entirely. This new era would last for 250 years. Generation after generation would live and die without knowing war. But what role would the samurai play in a Japan at peace? The fierce but educated warriors now became administrators. They oversaw rice production, wrote laws, and sometimes served as judges. There was however to be an even more profound transformation. A new and great ideal would be created.

The code was called Bushido, the way of the warrior. The concept that honor is more important than life itself remained, but the concept of honor was enlarged. Honor now included taking responsibility for the well-being of society as a whole. The new ideal would eventually be severely tested. On July 8th, 1853, two and a half centuries after Japan had closed itself to foreigners, a small squadron of ships from the United States Navy sailed boldly into Tokyo Bay. The Americans delivered an ultimatum: Open Japan to trade, or suffer the consequences. The samurai were indignant but helpless against modern ships and guns. Faced with the threat of western domination, the samurai knew Japan had to become powerful by becoming modern as quickly as possible.

To clear the way for modernization, the samurai who as individuals had always been ready to face death, now decreed the death of the entire samurai class. Traditional dress was discarded, ancient samurai privileges surrendered. Japan would be like other countries, with a constitution and a Monarch. The emperor was restored as the head of the government. The samurai disappeared, but their legacy would emerge in a terrifying new form. By the early years of the 20th century, samurai ways were largely forgotten, discarded relics of an outmoded past.

Japan had plunged into modern life, but the new outlook included a dangerous new ambition. Japan’s leaders now dreamed of conquering a vast overseas empire. To rally patriotic fervor, the ancient samurai legacy was invoked. All Japanese must be ready to fight with the samurai’s unrelenting courage and self-sacrifice. As Japan invaded Manchuria in 1931, and then China, army officers carried swords like those the samurai had used. With Nazi Germany dominating Europe, the Japanese believed there was only one power which could stop them from conquering all of Asia.

The Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor was carried out in an attempt to destroy America’s ability to fight in the Pacific. As Japanese forces continued their sweep through Asia, they imposed a rein of terror. The proud samurai sword was used to murder civilians and prisoners of war. Some believed this was a fulfillment of the noble samurai legacy, while others considered it a perversion of Bushido. As the Americans took the offensive and the tide of the war turned against Japan, a basic tenant of samurai tradition was fulfilled. Many Japanese surrendered, but many like the samurai, chose death.

By 1943, suicide had become a form of combat. Inspired by patriotism and the samurai ideal, they had become Kamikaze pilots, pilots of the divine wind. Their mission was to attack not with bombs but with themselves. Deliberately they crashed their planes into the American ships. Finally, in August 1945, the Americans unleashed the weapon that brought the war to an abrupt and terrible end. As Japan rebuilt itself, the heroic image of the samurai was restored. A resurgent film industry helped spread the ideal around the world.

The samurai tradition of courage and honor had been forged through nearly 800 years of warfare. Then in the centuries of peace, it was transformed into a code of service and justice. World War II had seen it tragically misused. What role will this proud legacy play in the future? The determination, self-sacrifice, and grace of this once remote and mysterious warrior class now takes it’s place in the history of this noble land.

Best Sellers

- Regular Price

- from $199.99

- Sale Price

- from $199.99

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $299.00

- Sale Price

- from $299.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $199.00

- Sale Price

- from $199.00

- Regular Price

-

$0.00

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $619.00

- Sale Price

- from $619.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $319.00

- Sale Price

- from $319.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $249.00

- Sale Price

- from $249.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $339.00

- Sale Price

- from $339.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $219.00

- Sale Price

- from $219.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $364.00

- Sale Price

- from $364.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $519.00

- Sale Price

- from $519.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per