History of Samurai Japan

Izanagi and Izanami with the heavenly jeweled spear

Throughout the course of human history, many of the greatest human civilizations have explained the origins of the earth in mythological terms. One typical creation myth is still told in Asia today. It tells of the goddess Izanami and her brother Izanagi, and how they dipped a spear into the ocean. When droplets of water fell from the blade they formed a group of islands to the east of the Asian continent, Islands that would become home to a remarkable and enduring civilization, Japan.

According to Japanese legend, the creative god Izanagi also created the Moon Goddess and the Sun Goddess. The grandson Ninigi then came down to earth to the island of Kyushu. Finally, in the year 660 BC, Ninigi’s grandson Jimmu became the first emperor of the people who spread from Kyushu to the Yamato Plain of central Honshu. Although this is the stuff of legends, it does contain a grain of truth. By 100 BC a young nation was establishing itself on the Yamato Plain. They were people of Asian origin who had arrived from the continental mainland some centuries before.

The aspects of Japanese civilization which are most appreciated and admired today may not be the same that people admired in Japan hundreds of years ago. For example, 400 years ago people thought of Japanese civilization as incredibly belligerent and strong. Nowadays when people think of Japan they think more about Zen, minimalism, peace, and harmony. We all know for instance that the Japanese are associated with very delicate gardens and that their love of nature is shown not only through paintings, statues, wood blocks, and other aspects of artistry that come down to us in the current day, but are visible through the whole of the last thousand years. This is influenced perhaps by Buddhism which has been such a strong part of the Japanese cultural tradition as well as its own native tradition of Shinto.

Portland Japanese Garden Creek

The first historical record of Japan is found in a Chinese document dated 57 AD. It describes a visit to China from a diplomatic young boy from the islands in the east. Over the following centuries, links between the two countries developed. It was the Chinese who called Japan the land of the rising sun, a name which over time evolved into Japan. Trade and commercial contact increased, and with it, the flow of cultural ideas. By the 6th century AD, a major Chinese religion had arrived on Japan’s shores. Now, the Japanese people already had a spiritual identity; they practiced an informal worship of a huge number of divinities, the Sun Goddess being just one of these. This local belief system became known as Shinto, or the way of the gods. This was to distinguish itself from the new Chinese faith, Buddhism. Buddhism would never eliminate the old beliefs completely but it did become a central feature of Japanese life. In the 6th century AD, Buddhism became very popular in the Japanese court. The emperor and also those at court thought this was an exciting and potentially influential new way to think about religion. Their enthusiasm was then spread from the official level down to the people. Shortly after Buddhism arrived it became amalgamated with Shinto.

Within decades of the arrival of Buddhism, temples were being constructed in the Yamato heartland. In 607 AD to the southwest of Nara, a Japanese prince founded the temple complex Hōryū-ji. In the early 620s, a condo or great hall, was added to the Hōryū-ji site and the first masterpiece of Japanese architecture was completed. Like all Japanese buildings at the time, the condo was made of wood. The Japanese islands were heavily forested and the use of brick was virtually unknown until modern times. Inevitably, many of these wooden buildings have failed to survive. However, the condo has managed to remain fully intact for fourteen centuries making it the oldest surviving wooden building. It’s spectacular simply on account of its antiquity and state of preservation, but it’s been able to survive because it was regarded right from the foundation as a very important structure. The condo reveals the influence of Chinese design. It’s a two-story building of post and beam construction topped with an elegantly curved ceramic tile roof in the style known as Irimoya. Inside is a wooden panel hall containing a priceless collection of bronze statues including the Shaka Trinity, a sculpture of Buddha surrounded by two of his saints.

Golden Hall and Five-storied Pagoda of Hōryū-ji

Around the time the condo hall was built, Buddhism was becoming the dominant feature of Japanese spiritual life. Soon, the new faith also began to influence secular affairs. Japan was now an established empire but it still had no permanent capital. According to Shinto belief, when an emperor dies, his successor has to find a new location to rule from. With the rise of Buddhism, this tradition was abandoned. In the year 710, the Japanese emperor established a permanent capitol at Nara. By the end of the century it had moved to Haira, now known as Kyoto. It would remain there for almost eleven centuries. But the emperor himself would enjoy little in the way of political power. Throughout Japanese history it has been powerful families, or clans, who have filled the positions of real authority. In the 9th century, the Fujiwara clan became the effective rulers, and the emperors gradually withdrew from political life. This division between the nominal head of state and the real source of power became established; a striking contrast to the situation in Europe where the king was very much the dominant figure.

The rule of the Fujiwara lasted until the mid-twelfth century. Many Japanese considered this to be a golden age. Contacts with China faded as Japan developed its own national identity but ideas from the mainland were still influential. New strains of Chinese Buddhism arrived. The Shingon sect proved especially popular and in the middle of the tenth century the Shingon temple complex of Daigo-ji was constructed at the foot of Daigo. Its most distinctive feature is a wooden structure that has survived to this day; a wonderful example of the most distinctive of Buddhist temple buildings, the pagoda. A pagoda is based on an original type of Nepalian architect called a stupa. Its original purpose was to contain relics of the Buddha. When Buddhism spread from China into Japan these stupas, which became known as pagodas, were used for holding Buddhist masses and religious ceremonies. Chinese and Japanese pagodas are distinctive because their shape involves a certain number of towers which are almost always an odd number. All except one that are surviving today are made of three or five stories. The reason for odd numbers is not entirely clear, but its possibly intended to suggest that perfection has not been reached. The popularity of the Shingon strain of Buddhism lead to the construction of many pagoda buildings. The Daigo-ji remaining the greatest surviving example.

Daigo-ji's five-storey pagoda built in 951, Kyoto Prefecture

The 11th century saw some of Japans greatest artistic triumphs. Another strain of Buddhism was now proving popular, Shin Buddhism. Central to this was the figure of the Amida Buddah whose name would be chanted in halls built in his honor. Some of these are among the finest of Japanese architecture, and the most famous, Amida Hall, was completed in 1053. It can still be admired at a site midway between Nara and Kyoto. This memorable building was part of the monastery known as Byōdō-in, the Phoenix Hall. The name derives from the layout of the building. On either side of the central hall are L-shaped wing corridors. To the rear is the tail corridor that gives the whole structure the appearance of a phoenix in flight. To the front of the hall is a small lake which reflects the architecture and adds to the overall sense of peace and harmony. This is a building which reveals an increasing distinctive Japanese identity, but its allure is not restricted to the exterior. Inside the hall is a golden statue of the Amida Buddha himself. The Phoenix Hall is one of the most distinctive examples of the worship of the Amida Buddha. It depicts the Buddha in the pure land of paradise, symbolized as being separated from the secular world by a large canal outside of the hall. In that sense, it’s symbolic of Buddhist separation from the profane world. The Phoenix Hall can be seen as a symbol of a confident 11th century nation.

Byodo-in Temple on the island of O'ahu at the Valley of the Temples

At the time it was built, the Fujiwara clan were Japan’s rulers and they would maintain control for another hundred years, but in the early decades of the 12th century, potential rivals began to emerge; the Taira of the southwest and the Minamoto of the east. In 1158, civil war broke out. Two years later, the Taira defeated the Minamoto and ousted the Fujiwara from power. But the Minamoto were not vanquished. In 1180, their leader Yoritomo led an uprising in the east. Five years of bloody conflict later, he emerged victorious and another age of Japanese history had begun. With the emperor still in place at Kyoto, Yoritomo set up his headquarters at the coastal town of Kamakura near present-day Tokyo. In 1192, he was heralded as the Barbarian-Quelling Great General, a title more commonly referred to as Shogun. Yoritomo was the first of the Shoguns.

Minamoto Yoritomo on his horse

These Shoguns would rule Japan for almost seven centuries but for the first half of this period they presided over a divided nation. Japanese society was highly futile, with the state-owning barons ruling on their own territory. Inevitably, disputes arose between rival lords and conflict became a constant feature of Japanese life. A professional class of warriors began to emerge, a body of fighting men forever associated with Japan, the Samurai. Originally, the Samurai’s role was that of a policeman; employed by a lord to protect his land and property. The word itself derives from the verb Saburai meaning ‘to serve’ but as Japan grew to be a military state, the Samurai became a warrior class in their own right. They sought to become revered warriors and possessed their own code of honor, the code of Bushido. Bushido, meaning the way of the warrior, was a system of thought that emerged during the medieval period at a time when Japan was riven by civil war. The basic idea comes from Zen Buddhism. It is the idea that the true warrior, Samurai, should not be concerned by the various petty doings of the world and that includes the fear of death.

Samurai in armor, 1860s. Hand-coloured photograph by Felice Beato

The Samurai displayed courage, endurance, and loyalty in the name of Bushido. But it is for their prowess in battle that they are best remembered today. In appearance, the individual Samurai was a formidable sight to behold. His armor contributed strongly to this. Overlapping iron plates were joined with colored cord to create a protective skin. On top of this, further protection was provided by a breast plate, iron gauntlets, leg shields, and a neck collar. But this body protection was more than just function, the overall design was often so intricately detailed that Samurai suits of armor are considered works of art in their own right. This is also the case for the Samurai’s weapons, especially the instrument of battle that the individual warrior treasured most, the Samurai sword. A Samurai actually carried two swords, with the shorter blade intended for the execution of ritual suicide, or seppuku if the code of Bushido demanded it. But it is the fearsome Samurai battle sword that impresses most today. This was the weapon that was central to the identity of the Samurai warrior. His soul was believed to be present within it and the craftsmen who made these weapons were believed to have supernatural powers. The sword, like the armor, was a creation of genuine beauty though it was primarily a devastating weapon; a single stroke of the blade could cut a man in two.

The making of swords in medieval Japan was not just considered a type of manufacture; it was actually a type of art. The Japanese were the first people in the world to use carbonized steel rather than ordinary iron to make their swords which tempered the steel and made it much harder and finer. This contrasts with western swords which are incredibly strong but have no flexibility. If you hit them in the wrong angle they can easily shatter. In contrast there is the Islamic sword which is very light and flexible but can’t cut through armor. The Japanese sword combines these two features in what appears to be a genuinely indigenous piece of technology. The techniques of beating down the steel until it produced a very fine blade and point were exceptionally developed. Even today there are many schools of sword making which have their own various masters and methods that are regarded as the products of apprentices who must learn their trade over many years. Of course over the more contemporary period, they do not use the techniques which are used in the 18th century to test the swords, which were cutting off the heads of executed criminals in attempt to see how fine the blades actually were.

Kuninobu forging swords with Masahiro as sakite

In the first half of the 18th century, weapons like this were used in combat time and again. There were so many armed disputes between the futile barons that warfare was effectively a national industry. But before the century was up, Japan faced a threat to its existence as a whole; a threat that would require the Samurai to fight together for a common cause. This was an enemy of the Asian mainland, the ever-expanding Mongol empire under the leadership of Kublai Khan. At the time, the Mongols controlled the greatest land empire the world had ever seen. By the 1260’s, their territories stretched from the Pacific to the Balkans. In the east, China and the Korean peninsula were already under Mongolian control and the islands of Japan were next in line for conquest.

In 1268, Kublai Khan sent a diplomatic message to the Japanese court of Kyoto. He demanded a huge payment of tribute with dire consequences if it was refused. In Kamakura, the military leadership decided to be bold. They simply offered no response to the Mongol leader. War was now inevitable. In November 1274, an armada of 800 ships left the Asian mainland carrying some 25,000 warriors: Koreans and Chinese along with their Mongol commanders. Fortunately for the Japanese, this invasion fleet was forced to withdraw in the face of a typhoon. The defenders had won a respite but they knew it would be temporary.

General Tsunesuke Shoni and Hisatsune Shimazu

Kublai Khan was bound to try again and this second attack came during the summer of 1281. Japan now faced a defining moment in its history. This time, the invasion force was stupendous. As many as 150,000 men may have set sail from the mainland with the Mongols again joined by Korean and Chinese allies. In June some 3,500 ships appeared off the southwestern coast of Japan. Over the following two months, fierce fighting took place as the invaders sought to establish bridge heads. In places like the Shiga peninsula they succeeded and the Japanese found themselves pushed back into the interior. But now, the weather intervened once more. On the afternoon of the 15th of August 1281, a ferocious storm struck the coast of Kyushu. Hundreds of Mongol ships were destroyed as others sought desperately to withdraw from the fray. The troops, already ashore, were now isolated and the Samurai warriors cut them down without mercy. Only a tiny fraction of the huge invading force ever returned home and Japan had won a decisive victory. The Mongols would not return.

Woodblock print of The Great Wave off the coast of Kanagawa, Katsushika Hokusai, about 1831 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Afterwards, the Japanese people gave the typhoon a name that is now familiar well beyond their shores. They called it the divine wind, the Kamikaze. Kublai Khan, the Mongol leader of China at the time, would have had a very good chance to take over Japan in 1281 if his invasion succeeded, however the lucky chance of the storm which destroyed a large amount of the fleet meant the invasion was no longer practical. By the time Kublai Khan had managed to produce another fleet of soldiers, he simply did not have enough time and attention to be able to mount the kind of concerted effort an invasion would have needed. In effect, the high point he had at 1281 was lost because of the storm. The fact that Japan didn’t fall under the invading force of the Asian mainland became a myth that Japan was a divine country, and that it was protected by the Kamikaze. 1281 is still remembered fondly by the Japanese people and remains a defining moment of their history.

The triumph over the Mongols did not lead to a great age of peace. Resentment built up against the Hōjō clan who now ruled the country, again the issue would be settled by war. By 1336, a new Shogunate had established itself, the Ashikaga. This was the beginning of an age named after the suburb of Kyoto where the new military leadership had made its headquarters. This was the Muromachi era. In many ways the age of Muromachi saw Japanese life continue as it had for centuries. The figurehead emperor still sat at the center of the Kyoto court. Local conflicts continued to engage the Samurai warriors, and the Buddhist faith remained central to Japanese spiritual life. This was also a time when a new strain of Buddhism began to emerge, Zen Buddhism. Zen had first arrived from China during the Kamokura era, but it was in the 15th and 16th centuries that it had made its most substantial impact in Japan.

Reverend Taka Kawakami. Photo courtesy of Rev. Taka

In the 16th century, the increasing popularity of Zen inspired many activities that are amongst the best known features of the Japanese way of life. Some of which were flower arranging, tea ceremonies, and landscape gardening. Across the Japanese islands can be seen examples of these tranquil, almost understated gardens. Near the middle of the 16th century, the period of Zen Buddhism had established itself in everyday Japanese life. The surviving tea ceremony buildings and landscape gardens show its influence. But Japan was about to be introduced to a totally new approach to the business of living, and to that of faith in particular. Europe was about to make its mark on Japanese history.

In 1542, a sailing ship was wrecked on the coast of Kyushu. It was a Chinese ship, but amongst those who scrambled ashore were three mariners from a nation on the other side of the world, Portugal. This was the very beginning of contact between Europe and Japan, and first impressions were mutually favorable. The Portuguese sailors admired what appeared to be an extremely advanced Japanese civilization. For their part, the Japanese were interested in the muskets and firearms carried by the Europeans. It soon became clear that the two cultures could do business with each other. During the years that followed, the Portuguese returned to Japan in increasing numbers. This was the European age of discovery, and soon Spanish and Dutch expeditions also arrived at this mysterious east Asian nation. Commerce drew them to Japan, but as well as European goods the trading ships also brought something else that soon infused many in the land of the rising sun, Christianity.

Portuguese carrack in Nagasaki, Nanban art attributed to Kano Naizen, 1570-1616

In 1549, a Portuguese ship arrived at the port of Kagoshima. Onboard was the legendary figure of the Christian faith, Francis Xavier. This Jesuit missionary had already spread the gospel through Indian and Southeast Asia. Now he began to preach to the people of Japan with remarkable results. Within two years, he had established a flourishing Japanese community devoted to an entirely new faith. Other missionaries followed Xavier’s example, and by the end of the 16th century, some 300,000 Japanese people had accepted the word of Christ. Many of the warlords in Japan found that by converting to Christianity, they would get the Portuguese and the Spanish, who were behind the Jesuits, on their side against the current rulers of Japan. In addition, the Christian philosophy was attractive to many of the Japanese who picked it up for the first time.

In the early years of the 17th century, the Japanese Christian community continued to expand. By 1615, it was half a million strong. But times were changing; a new shogunate had been established in 1603, the Tokugawa based in Edo, the city now known as Tokyo. The new military leader was Tokugawa Ieyasu, a giant figure of Japanese history. Ieyasu suspected that the Christian invasion of Japan would lead to European political domination of his people. In 1614, Christianity was officially banned. A quarter of a century of persecution and martyrdom followed, until in 1638 the 37,000 christians who remained found themselves besieged near the port of Nagasaki. When the siege was broken, virtually all were slaughtered. The Christian faith had survived less than 100 years.

Christianity Martyrs of Nagasaki, 16-17th century Japanese painting

The 1638 slaughter of the Christians was a major historical event. It marked the beginning of two centuries in which Japan was completely isolated from the outside world. Trading ships were all but banned and traveling abroad was made virtually impossible for the Japanese citizens. In addition, the Tokugawa consolidated their power further. The Japanese state had now become centralized and unified. This was a very different kind of political situation. Instead of almost continuous warfare between individual futile territories, Japan now enjoyed a long period of peace. The Tokugawa shoguns devised a cunning way to maintain the status quo; all futile lords were required to spend every other year at Edo where the shogunate could keep an eye on them. In the intervening years, they were forced to send their wives as hostages. The system worked and the Tokugawa endured until the industrial age. Though Japan was now isolated, the country did not stagnate. The years from 1603 until 1867 saw substantial advances in Japanese social and cultural life, and one of the most remarkable of all Japanese architectural achievements.

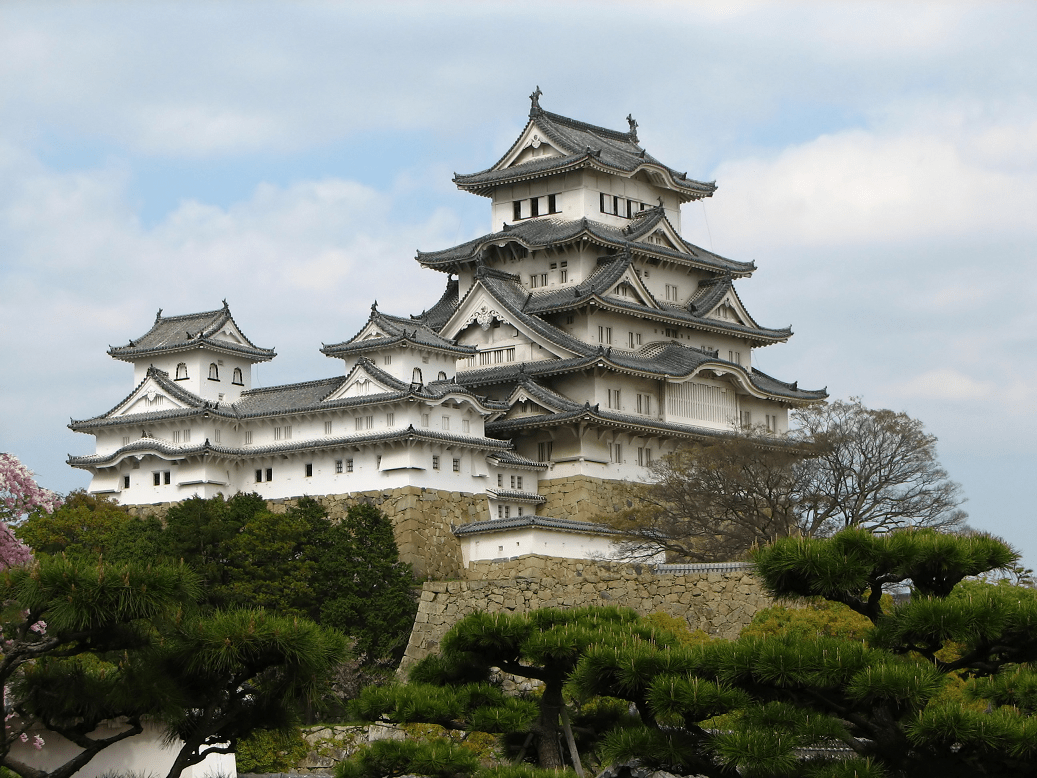

In the 14th century, the practice of castle building had become established as warfare continued to rage throughout the country. One such castle was constructed at Himeji, 25 miles to the west of Asaka. But in the late 16th century, the arrival of firearms meant that a more formidable defensive structure was required. In 1601, the lord of Himeji ordered the construction of brand new fortifications. Nine years of enormous effort later, the work was completed and the result was one of the greatest monuments in the whole of Japan, Himeji Castle. The castle consists of a main tower and three subsidiary towers. The main tower is built on an impressive platform of rock which also contains the two basement floors of the seven story structure. The building is again mainly constructed from wood, but this did not compromise the defense of Himeji castle, or make it less fortified then stone built European equivalence. The entire construction is protected by a mote, walls of stone, a bewildering number of turrets, hiding places, tunnels, watch towers, and no less than 84 castle gates. It was, and remains, a powerful defensive structure but Himeji Castle can also be admired for its graceful appearance. Its architect brought the same degree of natural elegance to this military building as his predecessors achieved with their religious constructions. It’s the second biggest castle in Japan exceeded only by the major castle in Osaka. It has over 50 turrets most of which are considered items of great artistic beauty. In the 400 years that Himeji castle has stood, its military significance has been secondary to its beauty. Its completion coincided with the end of internal Japanese warfare. In the centuries that followed, the Tokugawa presided over a nation at peace, and wonderful buildings such as this were used as grand residencies.

Himeji Castle located in the center of Himeji, Hyōgo

This new age of peace meant less of a role for the famous Samurai. With no wars to fight, many drifted into the expanding cities such as Edo. By the 18th century, the urban center that is now Tokyo was the biggest city in the world and many former Samurai found themselves living there. Some were able to flourish in new roles, such as the civil service or teaching; others disappeared into the twilight world of Ukiyo, or urban nightlife. In 18th century Edo, this Ukiyo was an indulgent world where many succumbed to the temptations of strong drink. Others sought out the comforts of the Geisha girls who became established around this time. Many contemporary artists chose this world of the night as the subject matter for their distinctive woodblock prints. This was the so-called Ukiyo-e style of painting which reached its peak around 1800 with the work of Kitagawa Utamaro. The Ukiyo-e woodblocks gives us an insight into the ordinary lives of Japanese townspeople during the Edo period of the 16th to 19th centuries. To that extent, they reflect the Ukiyo, the unofficial world of the artists and the pleasure quarters of cities like Edo where people went for entertainment and to unwind after a hard day’s work.

Shijo Noryo - Cooling off at Shijo. From series '100 Aspects of the Moon' by Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, 1839-1892

The distinctive style of Japanese art would come to influence many artists in the western world, but this would not be until after Japan had finally ended its long period of isolation. In the 1860s, following pressure from the industrialized powers of the west, Japan finally opened itself up to the outside world once more. The shogunate came to an end and the emperor regained political power after eleven centuries. Japan now presumed the path of industrialization with astonishing speed. Within decades the Japanese had adopted industrial methods so effectively that they were able to defeat the might of the Russian navy. By the time of the second world war, the Japanese nation had become mightier still. Only the American atomic bomb brought an end to an empire that had conquered an enormous region of Asia and the Pacific. And though the Japanese were defeated, their national identity survived. The Japanese civilization remains one of the most remarkable on earth.

Best Sellers

- Regular Price

- from $199.99

- Sale Price

- from $199.99

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $299.00

- Sale Price

- from $299.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $199.00

- Sale Price

- from $199.00

- Regular Price

-

$0.00

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $619.00

- Sale Price

- from $619.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $319.00

- Sale Price

- from $319.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $249.00

- Sale Price

- from $249.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $339.00

- Sale Price

- from $339.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $219.00

- Sale Price

- from $219.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $364.00

- Sale Price

- from $364.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per

- Regular Price

- from $519.00

- Sale Price

- from $519.00

- Regular Price

-

- Unit Price

- per